This is the last in a series of 8 articles on checkout usability that combine findings from our checkout usability study and benchmark of the 100 largest e-commerce sites.

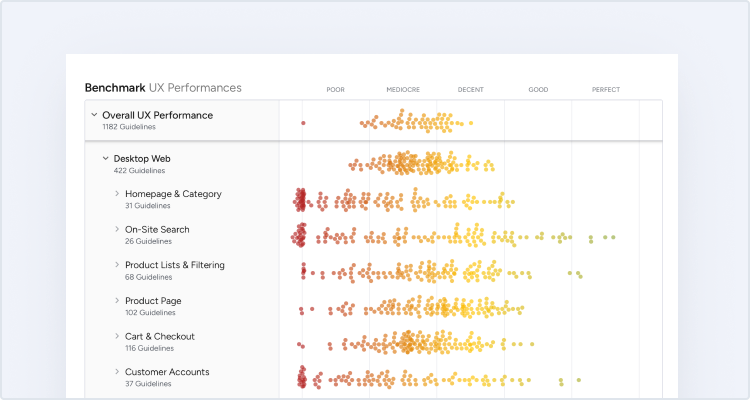

In this article we’ll analyze the checkout process experience at the top 100 e-commerce sites in the US across six checkout usability categories, identifying general problem areas and entire categories where even the very best sites leave plenty of room for improvement. Using the more than 6,300 checkout usability ratings in the benchmark database we’ve summarized the site scores across the six categories from the report to reveal their distribution.

For the last few years Jamie and I have conducted checkout usability studies, publishing one study as a report, written 29 articles on checkout usability here at Baymard, published four at Smashing Magazine, audited some of the top checkouts, and benchmarked the checkout processes of the entire top 100 grossing US e-commerce sites. Most of this work end up as specific advice and checkout design guidelines, but in this article we’ll take a more high-level view on the current state of checkout usability.

Distribution chart of checkout usability scores divided by category. Each summarized site score is plotted as a grey dot, along with a category average (marked X), the expected/theoretical average (O) as well as the theoretical minimum and maximum score of the categories (red and green triangle).

Data input – any kind of data input the customer must enter during checkout.

Copywriting – the use and wording of text throughout the checkout process.

Layout – the visual layout of the checkout pages.

Navigation – the implementation of process steps, buttons, and navigational links.

Flow – the flow between the individual process steps.

Focus – the site’s own business benefits vs. the customer’s shopping experience and privacy.

Getting the Basics Right

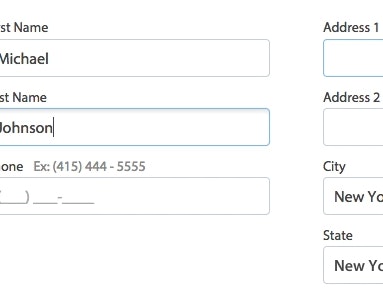

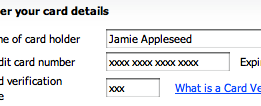

Already when conducting our first checkout usability study we saw a surprisingly large number of sites breaking basic usability guidelines. Common violations include: requiring users to register, not showing shipping costs until the review page, asking for the same information multiple times, weak design of credit card fields, lack of a clear primary button, non-linear checkout flows, etc. (Tip: we covered 11 of the basics in this Smashing Magazine article.)

Upon closer inspection of the checkout usability distribution chart there are multiple areas that stand out.

The actual average in the Data input category is significantly lower than the expected average – most sites simply have poor form field usability.

Most noticeably there’s a dramatic gap between the expected average (O) and the actual average (X) in the Data Input category. In other words, of the top 100 e-commerce sites the average site performed significantly worse than expected with numerous violations of even basic form field usability guidelines. Also notice how the site scores (grey dots) are much lower in the Data Input category compared to all other categories, with half the top 100 sites performing downright poorly, and the other half fairing only halfway decently. This is surprising (and frankly unacceptable) considering the wide availability of form field usability research.

The Focus category (business benefits vs. the customer’s shopping experience) isn’t a pretty sight either. However, this is less of a surprise than the low level of form field usability because many of the Focus guidelines are likely broken on purpose to reap short-term profits (despite the negative impact a degraded customer experience will have in the long run). A good example of such prioritization is a site’s newsletter option where half of the top 100 sites pre-check the newsletter box (even though the majority of users find this approach “sneaky”), and another third of the sites silently force-subscribe customers to their newsletter (with no way of opting out during the checkout process). Such implementation is bad for usability but hardly comes as a surprise considering the short-term business appeal.

The poor performance in both these categories certainly explain some of the industry average 69.80% checkout abandonment rate.

On the more positive end of the equation, it’s worth taking a look at the distribution in the Navigation category where the average site scores double the expected average. Navigational items and paths are generally well-designed across the top 100 e-commerce sites with many sites closing in on perfection in this particular category.

From Good to Great

Looking at the distribution chart we see that even the best sites has significant room for improvement in three of the categories: Data input, Layout, and Focus.

Even the very best sites in Data input, Layout, and Focus are far from perfect.

In these categories even the very best sites could still make a bunch of smaller changes to further improve the customer’s checkout experience. While these minor details won’t make or break the checkout experience on their own, they certainly can collectively (“many small streams make one big river”).

When asked directly, users may not be able to pinpoint the exact checkout problem they’re experiencing, but the more of these ‘minor’ guidelines you violate, the more likely it is that your customers will consider your checkout process “tedious”, “complex”, “stupid” or “slow” (just a few of the words used by the test subjects during testing).

However, the picture isn’t all dark and gloomy. In the remaining three categories we find examples of a few sites that are more or less flawless within a particular category. More specifically, Northern Tool scored close to perfect in Copywriting. Gilt did exceptionally well in Navigation. And Amway proved outstanding in Flow. (Do note that these site may have been near-perfect in their respective category but that’s not to say these sites had perfect checkout usability overall – they still violate crucial checkout usability guidelines in the other categories in their UX process.)

It’s Not About a Single Fix

Ultimately great checkout usability is not about a single guideline that fixes everything. It’s achieved by putting in place a solid foundation (“getting the basics right”) and then working on all the minor details (“from good to great”) that collectively end up having a significant impact on the checkout experience too. Make sure you get the basics right before focusing on the details.

Checkout processes are by nature heavy on form fields, so pay extra attention to form field usability. Nearly all top 100 e-commerce sites needed to focus more on data input (form field usability) during checkout. In fact, as we’ve seen in this article, even the very best e-commerce checkouts had plenty of room for improvement in this area (as well as Layout and Focus).