Key Takeaways

- Requiring users to use overly complex passwords will result in fewer users creating accounts, and more users being unable to immediately access their existing accounts

- The minimum required for password security should be 6–8 characters for most general e-commerce sites

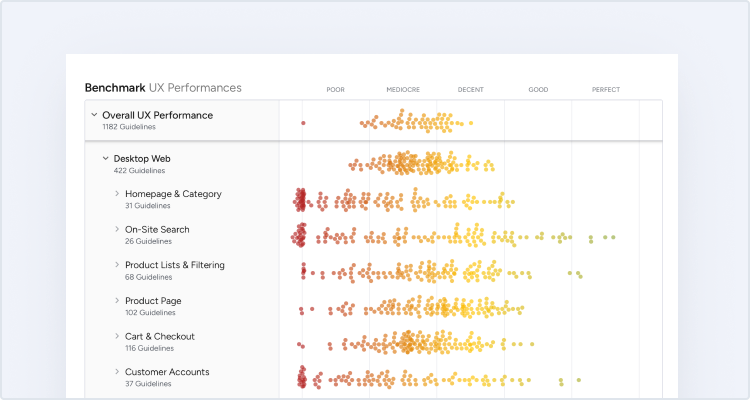

- Yet 82% of sites in our benchmark require unnecessarily complex passwords

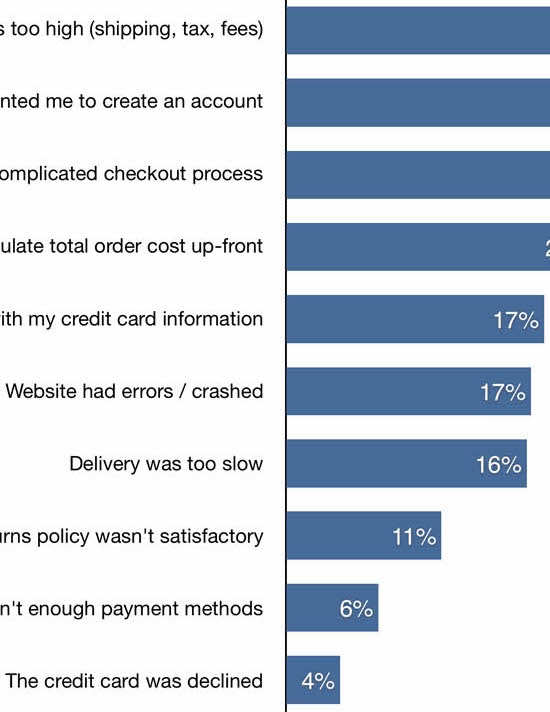

For many users, the need to remember and maintain a long and complex password is a key factor behind their reluctance to sign up for a site account.

Indeed, across multiple large-scale studies, we’ve observed that unnecessarily complex and strict password rules most directly harmed participants’ ability to actually sign in — sometimes even leading to abandonment when users were unable to remember or accurately recreate their complicated password.

In practice, too-strict password rules can drastically impact the checkout-completion rate, stymying legitimate returning users as much or more than would-be hackers. In some of our tests, existing account users on retail sites had an up to 18% checkout abandonment rate solely due to password reset issues.

Yet our e-commerce UX benchmark reveals that 82% of e-commerce sites have very complex password requirements — which inhibits new users from creating accounts, and limits existing users’ ability to access their accounts without significant friction.

In this article we’ll discuss our Premium research findings related to the UX of e-commerce account passwords:

- How unnecessarily complex password requirements cause issues for users

- How to implement a simple password requirement that most users will be comfortable meeting

- 2 ways to mitigate security risks related to unauthorized account access

How Unnecessarily Complex Password Requirements Cause Issues for Users

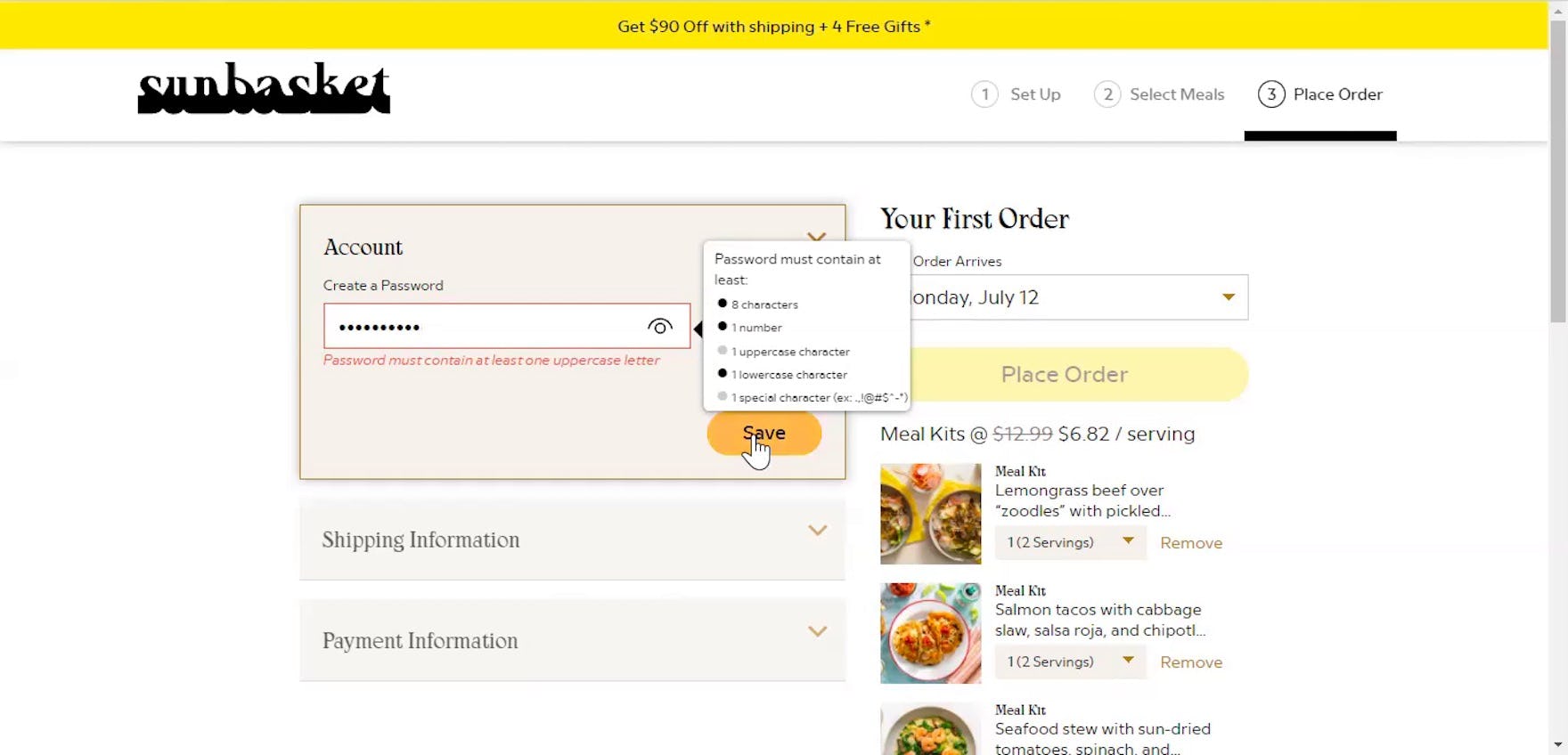

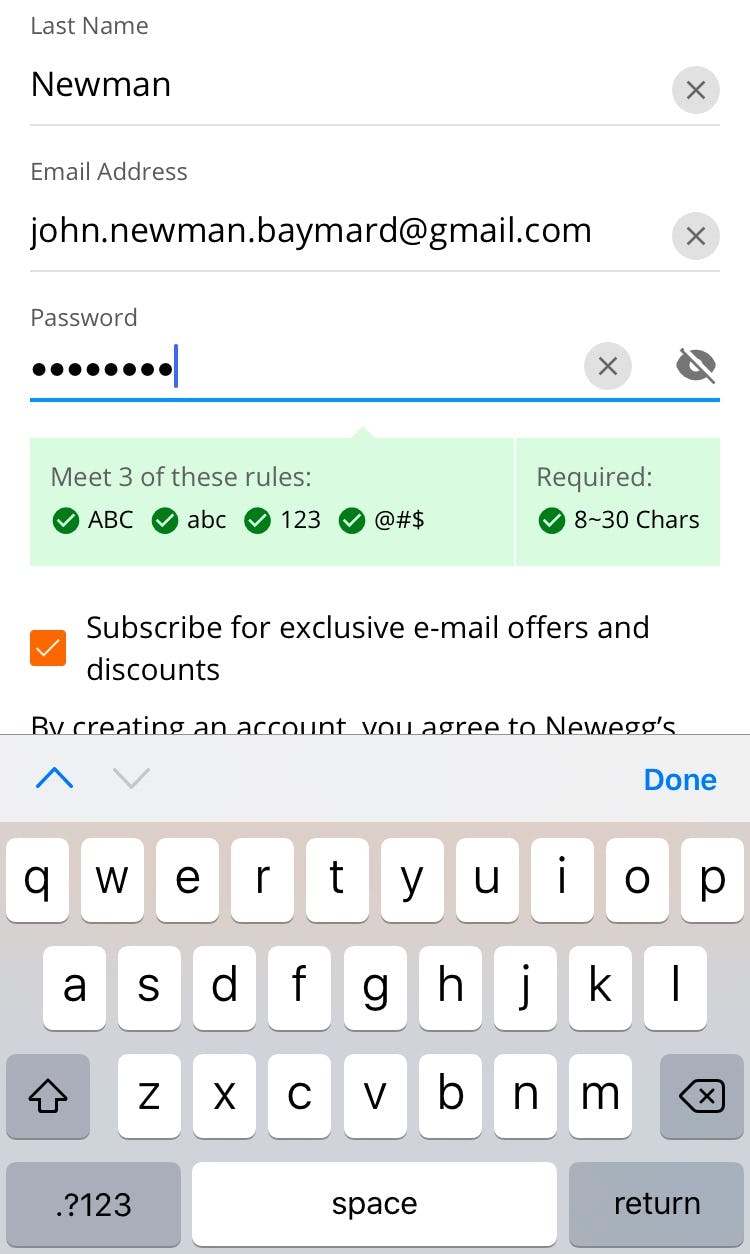

“It needs at least one lowercase letter, one uppercase letter. Are you kidding me?” This participant creating an account at Sunbasket was taken aback by the lengthy list of complicated password requirements, which forced him to reconsider his entry in order to comply and move forward. While users may be able to create a password that complies in the moment, remembering it later in order to sign in is another matter.

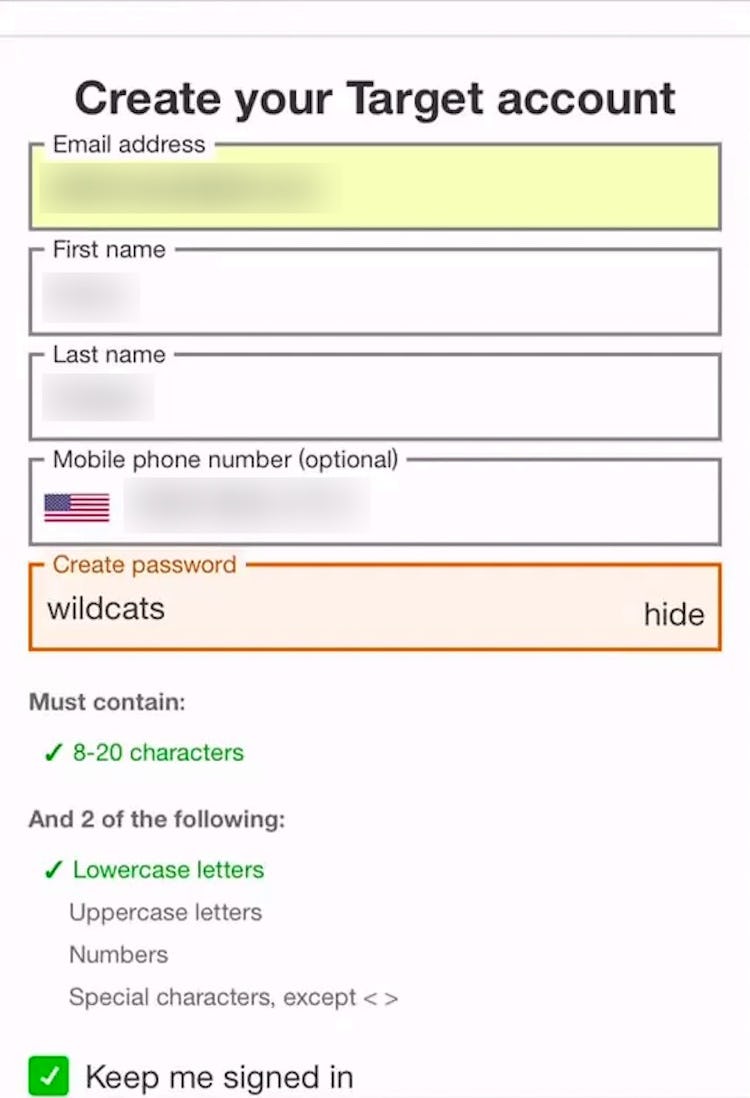

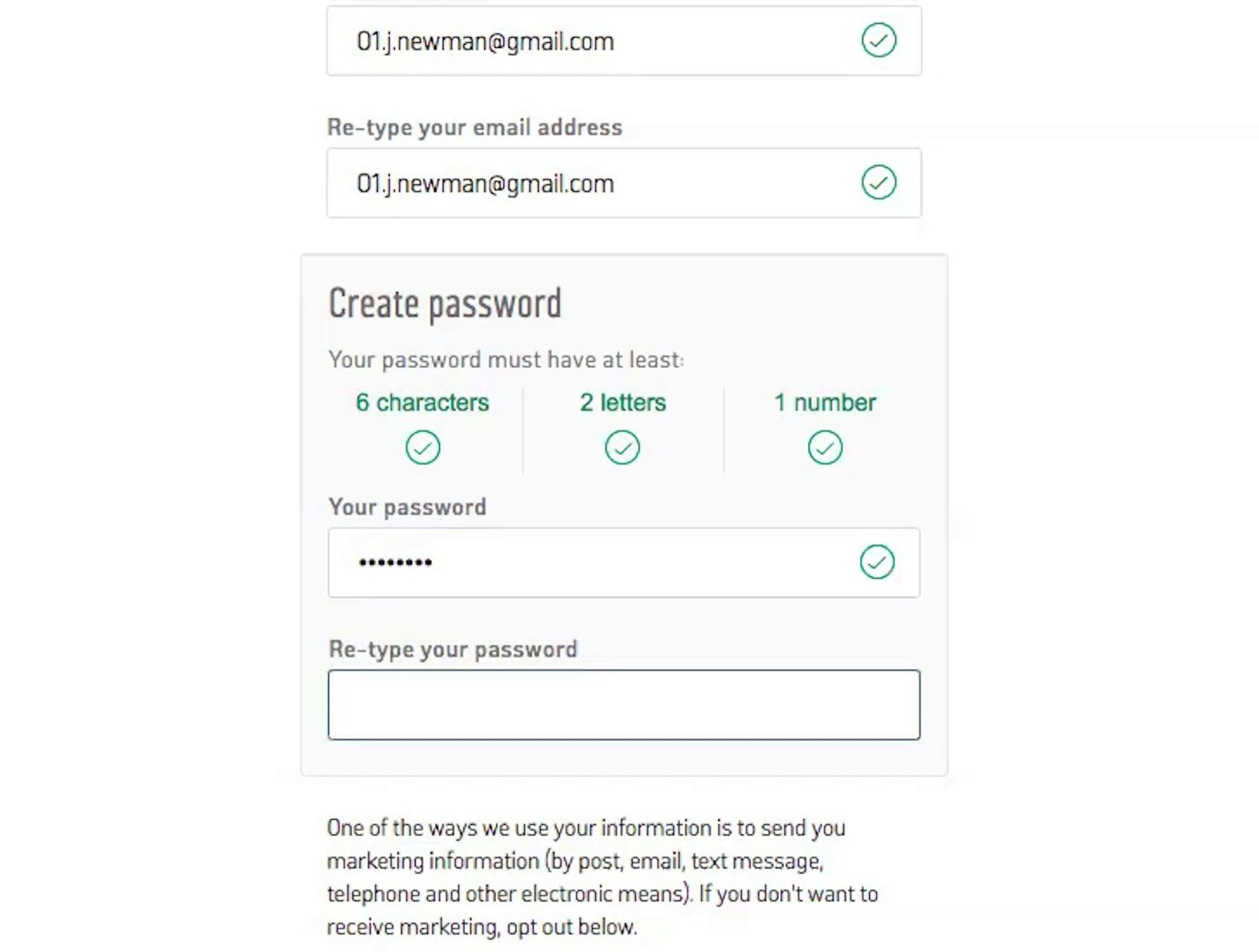

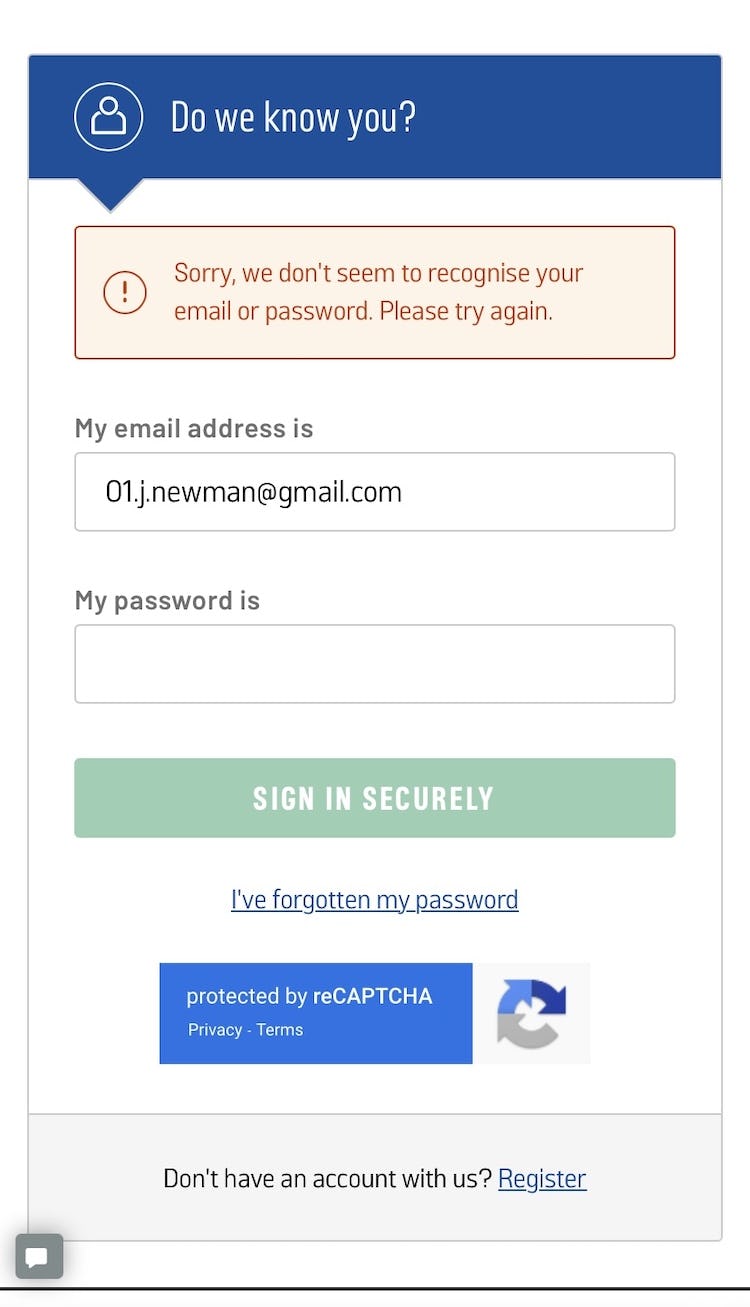

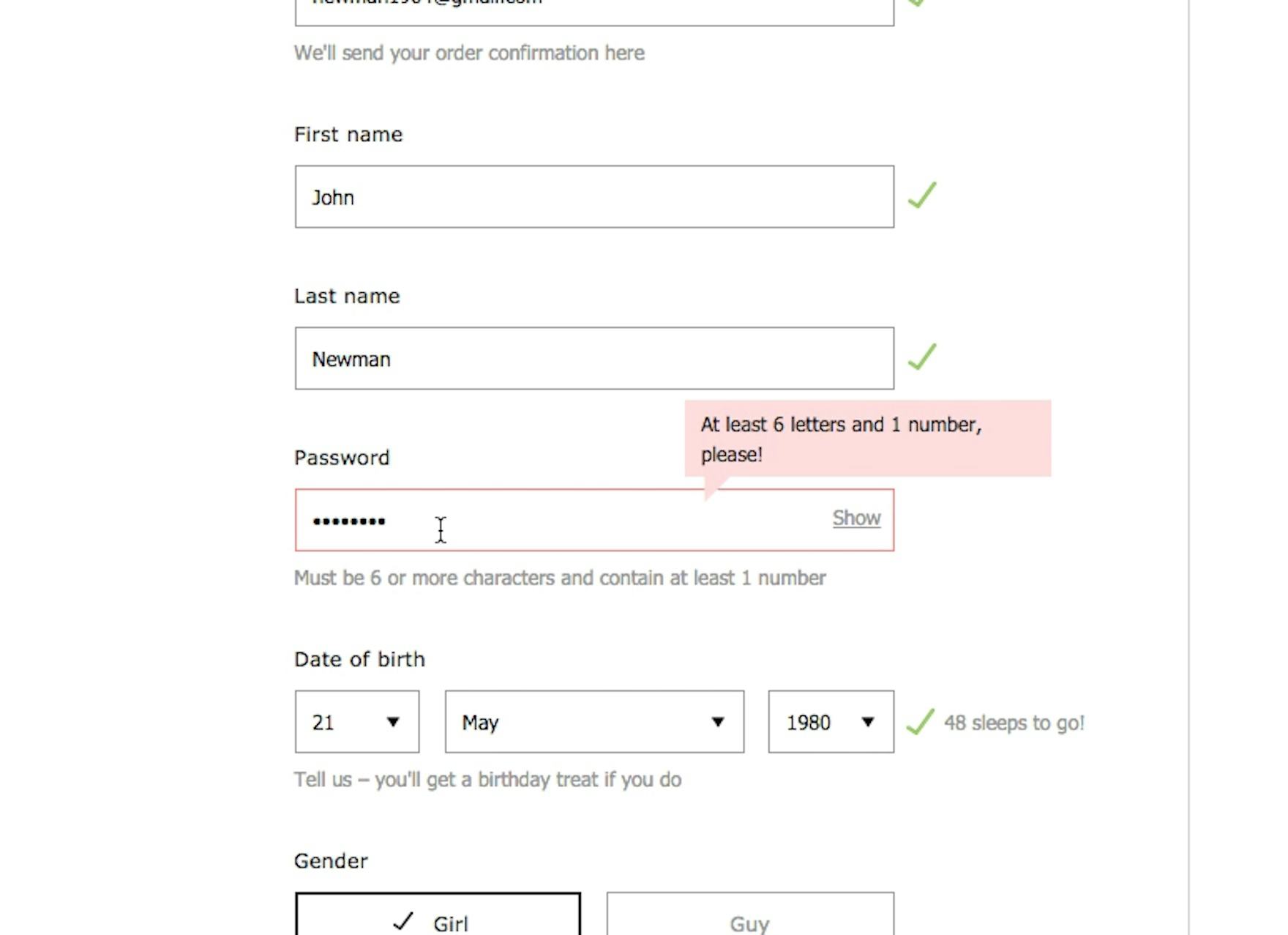

Although the password requirements on Argos (UK) are clearly shown (first image), they are still overly strict and may cause users unnecessary delay when attempting to sign in later (second image).

Across multiple rounds of usability tests, we’ve frequently observed participants become frustrated by lengthy, complicated lists of password requirements.

Despite this, we only rarely observe that complicated password requirements cause users to immediately abandon (as long as the password requirements are clearly communicated up front).

However, when measuring the impact of password requirements, it’s not the account-creation completion rate that matters most but rather the sign-in failure rate on subsequent site visits.

In short, the real risk of overly demanding password requirements is users’ inability to easily sign in later.

While users may be able to formulate an adequately complex password in order to “check all the boxes” when creating an account, their ability to recall from memory and successfully recreate it in order to sign in diminishes with each additional requirement.

Indeed, when attempting to sign in, users may strain to remember the very complicated password they were previously forced to create, leading them to try one or more of the following:

- Attempt to sign in with multiple password attempts

- Attempt again to sign in using multiple password and email combinations (for users who have multiple email accounts)

- Give up and initiate a password reset

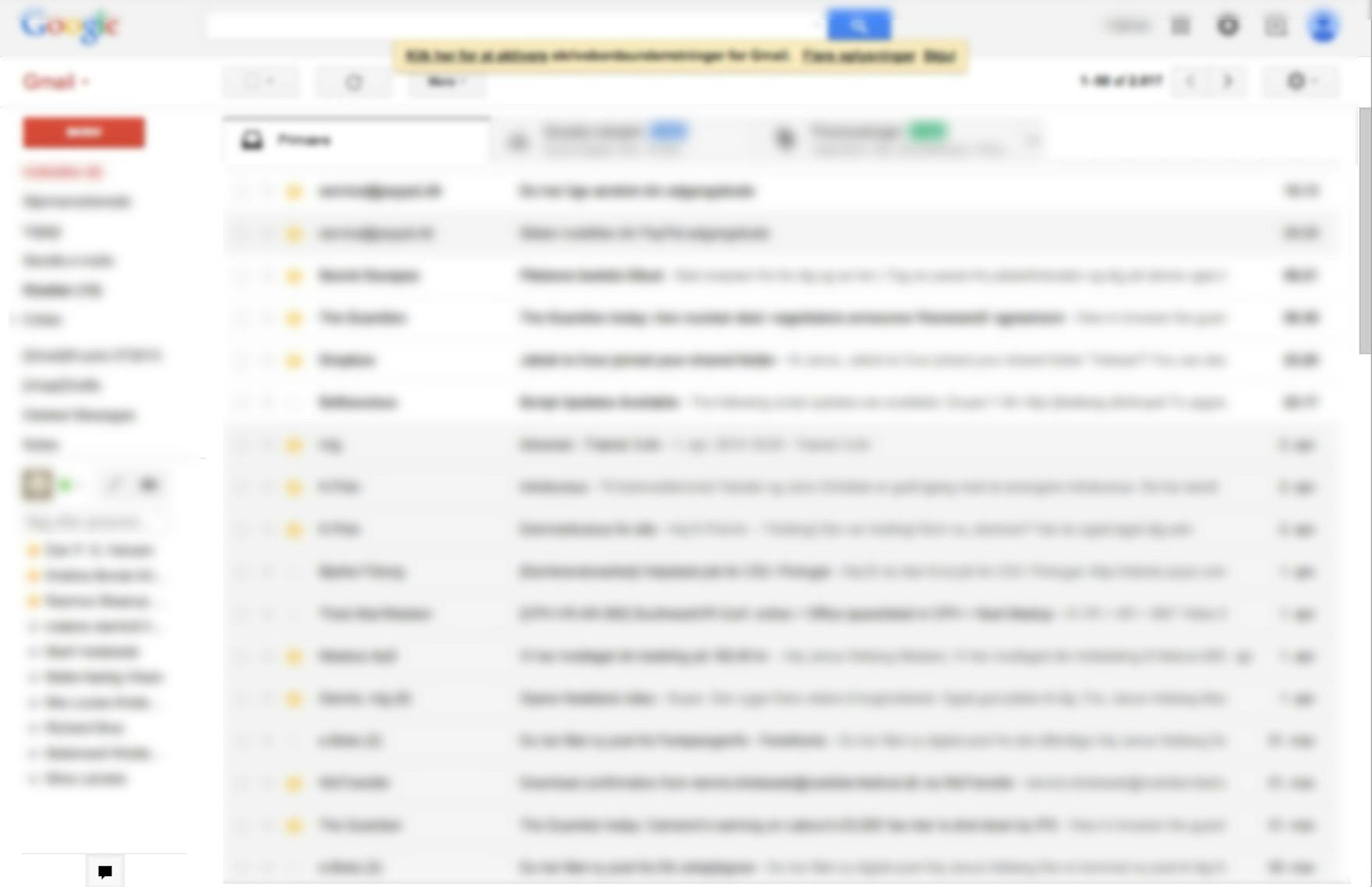

- Open their email client in a new tab or application

- Wait for the password-reset email (which first must be sent from the site’s outgoing email server and then be processed by the user’s incoming mail server)

- Click or tap a link to set a new password (where they often can’t use the previously used password)

- And finally return to the site — all before even initiating the checkout process

In effect, the convenience of having an existing account on the site — with a saved address and potentially saved payment information — shrinks substantially when considering this time-consuming and burdensome necessity just to sign in when users are unable to remember their previously created password.

“Normally I have some passwords that I use…I think it’s difficult to remember passwords, it’s quite a lot of them you have to remember. That is a pain…and there’s different requirements, and that’s why you can’t remember the passwords. Now I’m here wanting this t-shirt and have to come up with something right here on the spot, so it’s not going to be very well thought through.” A test participant complained about the password requirements at ASOS, which forced him to create a password that wasn’t his typical e-commerce password.

To combat the risk of forgetting their passwords, users may develop their own personal formulas or strategies for maintaining passwords across different sites (assuming they’re not using their browser or a password manager to remember their passwords).

For example, one participant from testing shared, “I have a code that I use for everything. It starts with a capital letter, then there’s six letters, and then it ends with two numbers…Sometimes the requirement is a capital letter, sometimes a number, so I have that one for all sites”.

Another shared his strategy as, “I use my city with a capital starting letter followed by the postal code, because then you have a capital letter, a long password, and a number, and then everybody is happy, and it’s relatively easy to remember”.

However, sites with very complex or novel requirements may force users out of using their “standard” passwords, further increasing the likelihood they have difficulties remembering it later and, consequently, experience sign in issues on subsequent visits.

Worse still, users’ reliance on such strategies to cope with “password overload” and remember the password on any given site risks that they inevitably fall back on options that make them easier to recall — whether reusing the same or overly similar passwords across multiple sites, writing them down in an insecure place (whether physical or digital), or implementing predictable rules (such as substituting “0” for the letter “o” in dictionary words).

“This is frustrating. Really, I’d have to consider if I should buy this, I think I’d consider if there were another place where I should buy it, and then go there. This is super frustrating.” This patient but frustrated participant waited over 6 minutes for his password-reset email to arrive, going back and forth to check the email address multiple times.

During testing, receiving the password-reset email was an especially problematic step, with many participants becoming frustrated and abandoning their task when password emails were delayed or caught in spam filters, or when they had separate issues with signing in to their email account in the first place.

Across all test participants who tried signing in to their private, preexisting accounts at large test sites like Amazon and ASOS, we observed that an unremembered password, followed by a password-reset process, caused a massive 18.75% average checkout abandonment rate — all due to “reset email” issues.

In practice, even one-time-use sign-in links (sometimes called “magic links”) that allow users to bypass parts of the traditional password-reset process are prone to these issues, which can entirely prevent users from being able to sign in.

How to Implement a Simple Password Requirement That Most Users Will Be Comfortable Meeting

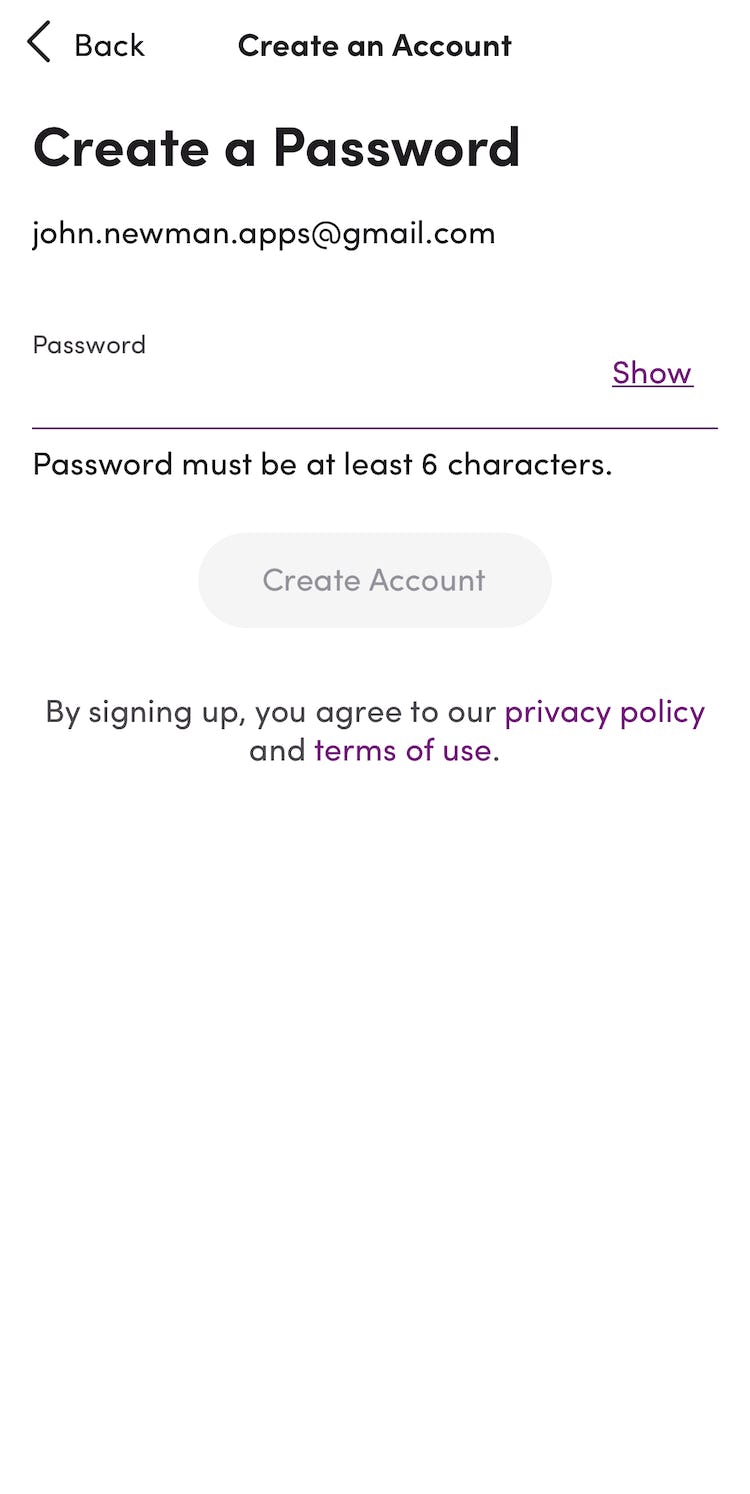

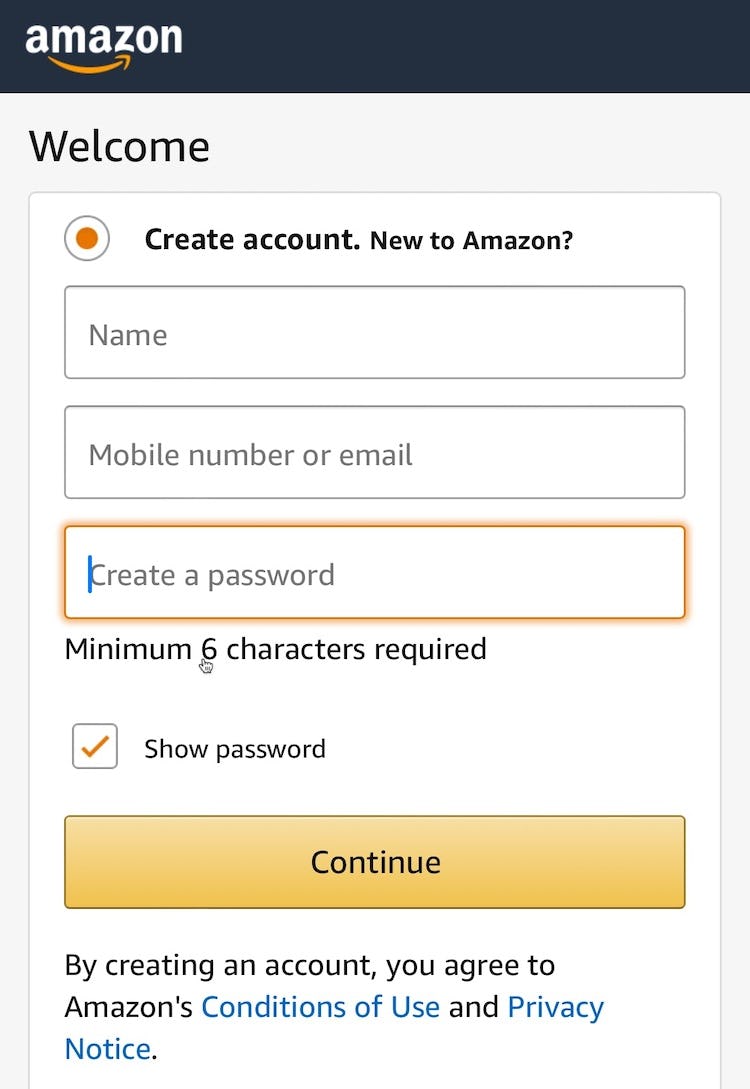

On Dollar Shave Club, the only requirement for passwords is a minimum of 6 characters.

Given the severe usability implications of too-strict password rules — and subsequent abandonments from account owners as they try to reset their password — sites should minimize the burden of password-complexity requirements, instead using technical solutions to defend against different kinds of attacks (see below for further discussion).

To make it easier for users to create and remember a password of their choice, sites should only impose a minimum password length, to prevent very short (and trivial to hack) passwords from being used.

Many online-security experts (e.g., NIST) recommend a minimum of 8 characters (or 6 if the password is machine generated), which provides a balance between increased security and being overly burdensome to users.

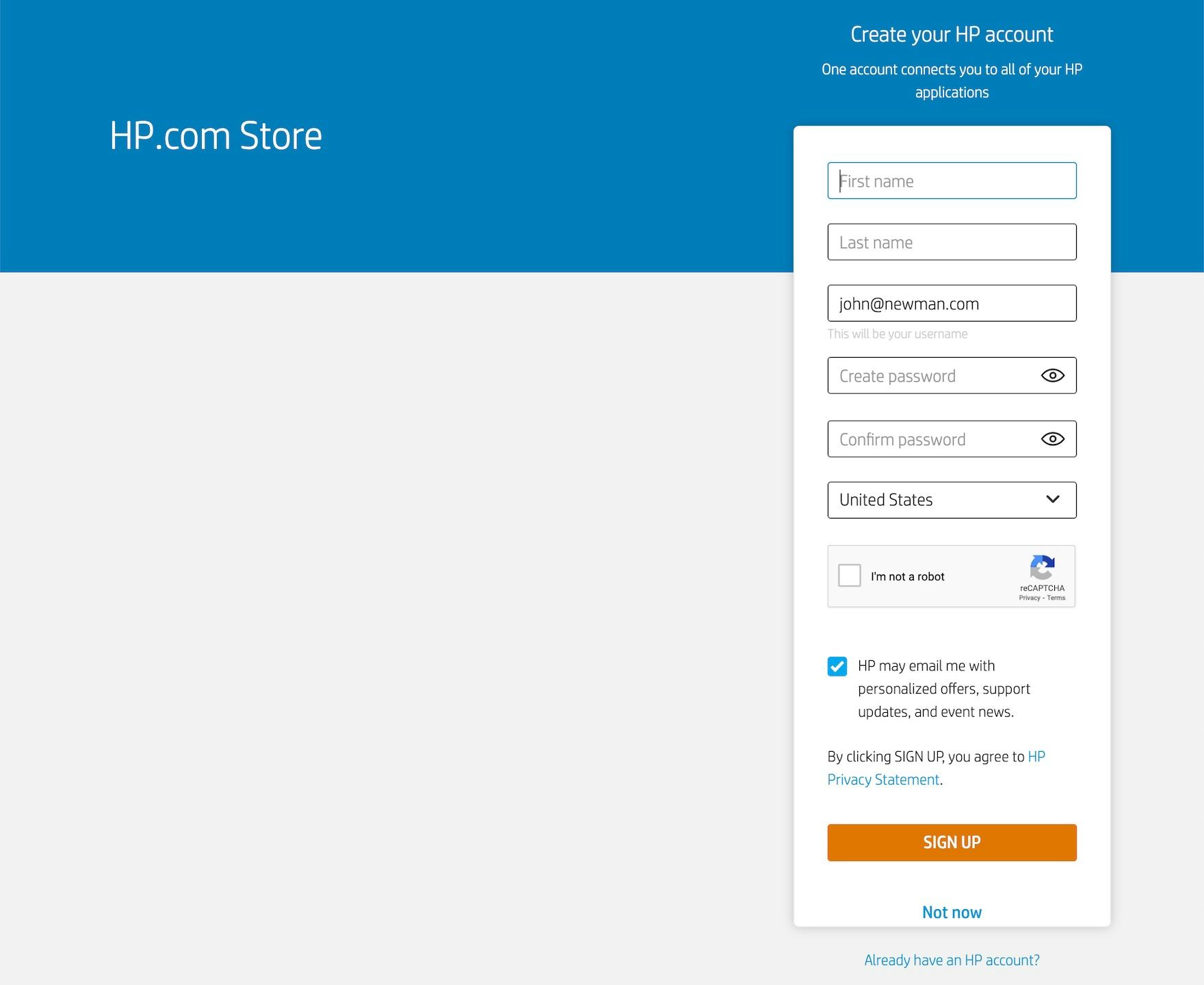

Importantly, sites should also avoid imposing input restrictions on passwords, such as only allowing certain special characters or having restrictive maximum password lengths.

Providing a great degree of freedom allows savvy users to adopt secure password strategies — such as using 16+ characters or, ideally, machine-generated passwords from a password manager app — without needing to worry that they don’t meet site requirements.

Ideally, password length should only be capped by the maximum allowed by the site’s back-end systems.

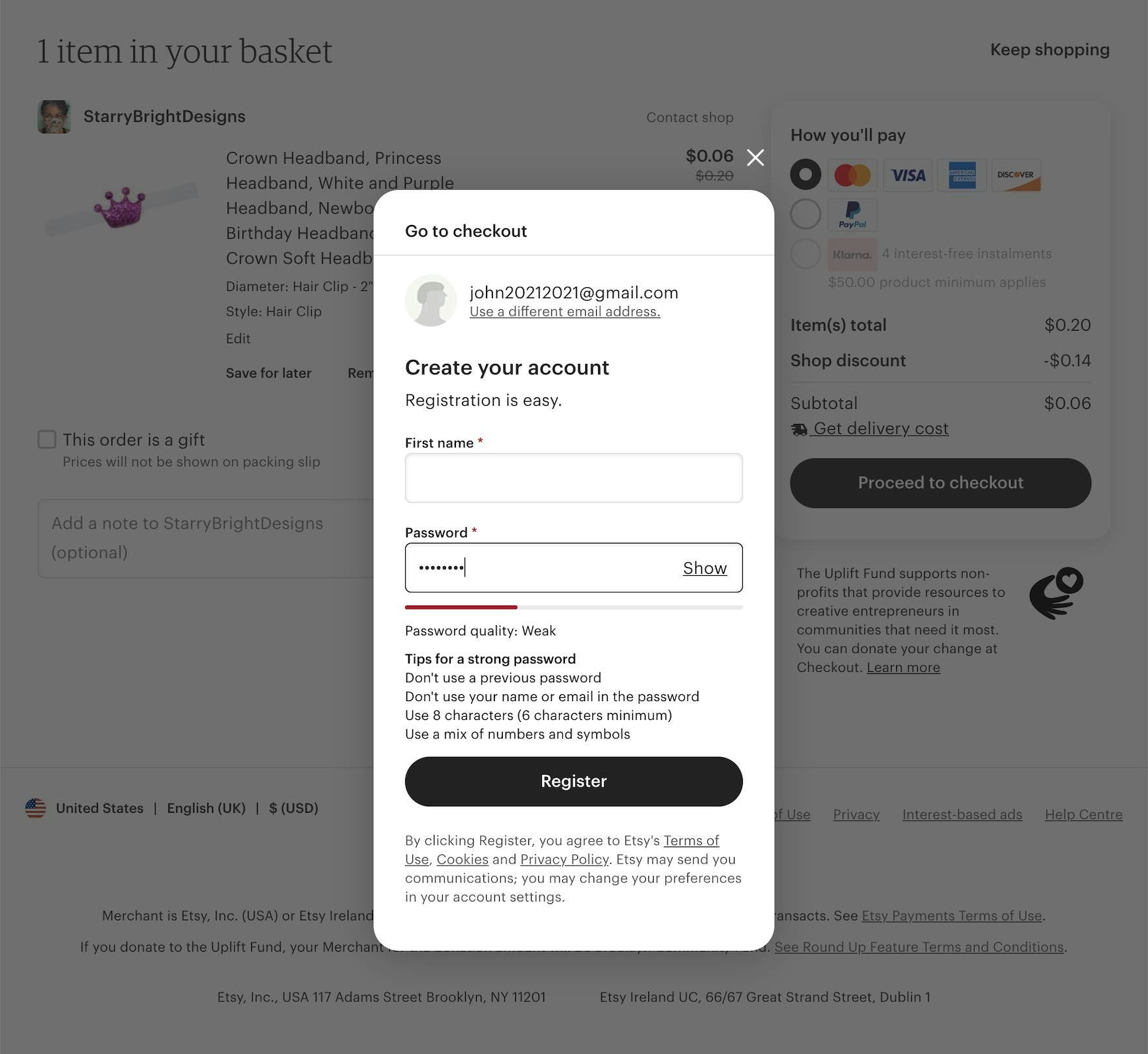

While Etsy provides suggestions for a strong password alongside a dynamic “password quality” meter, the only strict requirement for passwords is a minimum of 6 characters, allowing users to flexibly determine their own password.

While requiring further password restrictions risks users being unable to easily sign in down the road, sites can still encourage users to adopt strong passwords by suggesting a longer password be used, while still allowing users to proceed with a 6–8-character password.

This way, users can opt in to a technically more secure password without being forced to do so.

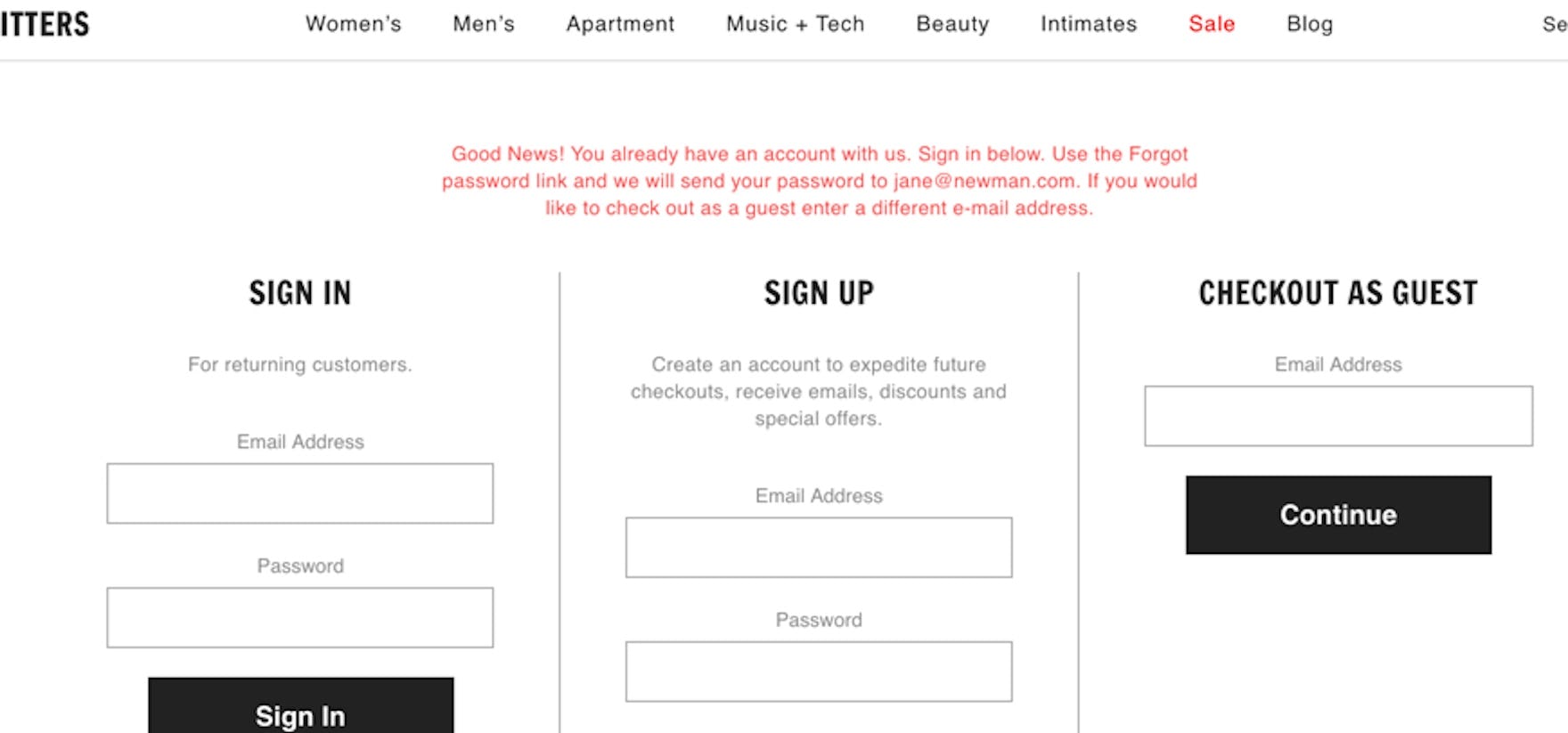

When sites prevent users from checking out as a guest if they already have an existing account (as seen here at Urban Outfitter’s), they ensure that any delay or issues with the password-reset process is guaranteed to cause nearly all users to abandon the site, as they are locked out from proceeding with their registered email address.

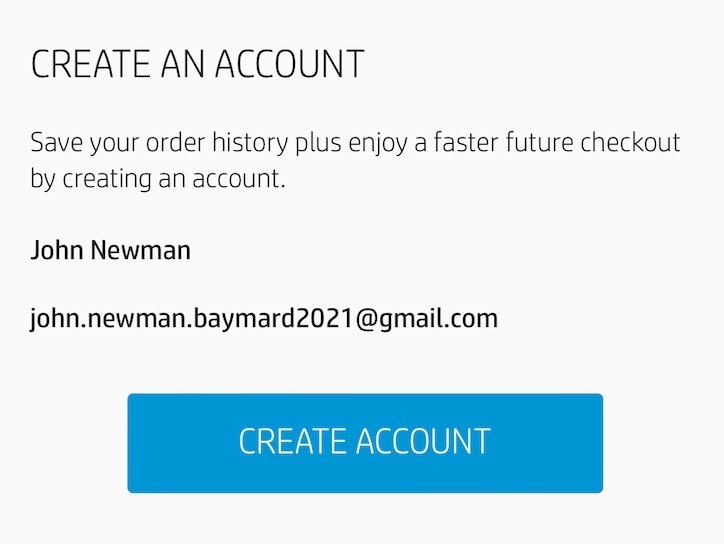

Additionally, to avoid password-reset issues from locking users out from completing their purchase, it’s vital that users can always do a guest checkout, even if their email is already tied to an existing account.

If users cannot perform a guest checkout in general, or cannot perform guest checkouts with an email that is already tied to an account, then sites in practice force all users to give up their purchase if there’s even the slightest delay or issue with the password-reset process.

2 Ways to Mitigate Security Risks Related to Unauthorized Account Access

While there remain tangible risks to poor account security, sites can take substantial steps to mitigate security concerns while removing the burden of overly complex passwords for users.

It is a prerequisite that e-commerce sites implement additional account security measures, like the two suggested in this section, before reducing the password requirements:

- Imposing password-attempt obstacles and limitations

- Requiring users to retype payment details if sending to a new address

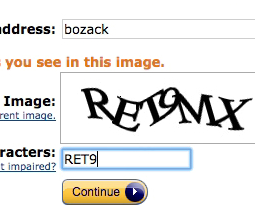

1) Imposing Password-Attempt Obstacles and Limitations

Foremost, sites can make it harder for would-be hackers to access existing accounts.

There are a variety of strategies sites can adopt, including throttling or limiting sign in attempts and implementing human-friendly CAPTCHAs to block brute-force attacks. (For more on these strategies, see NCSC.)

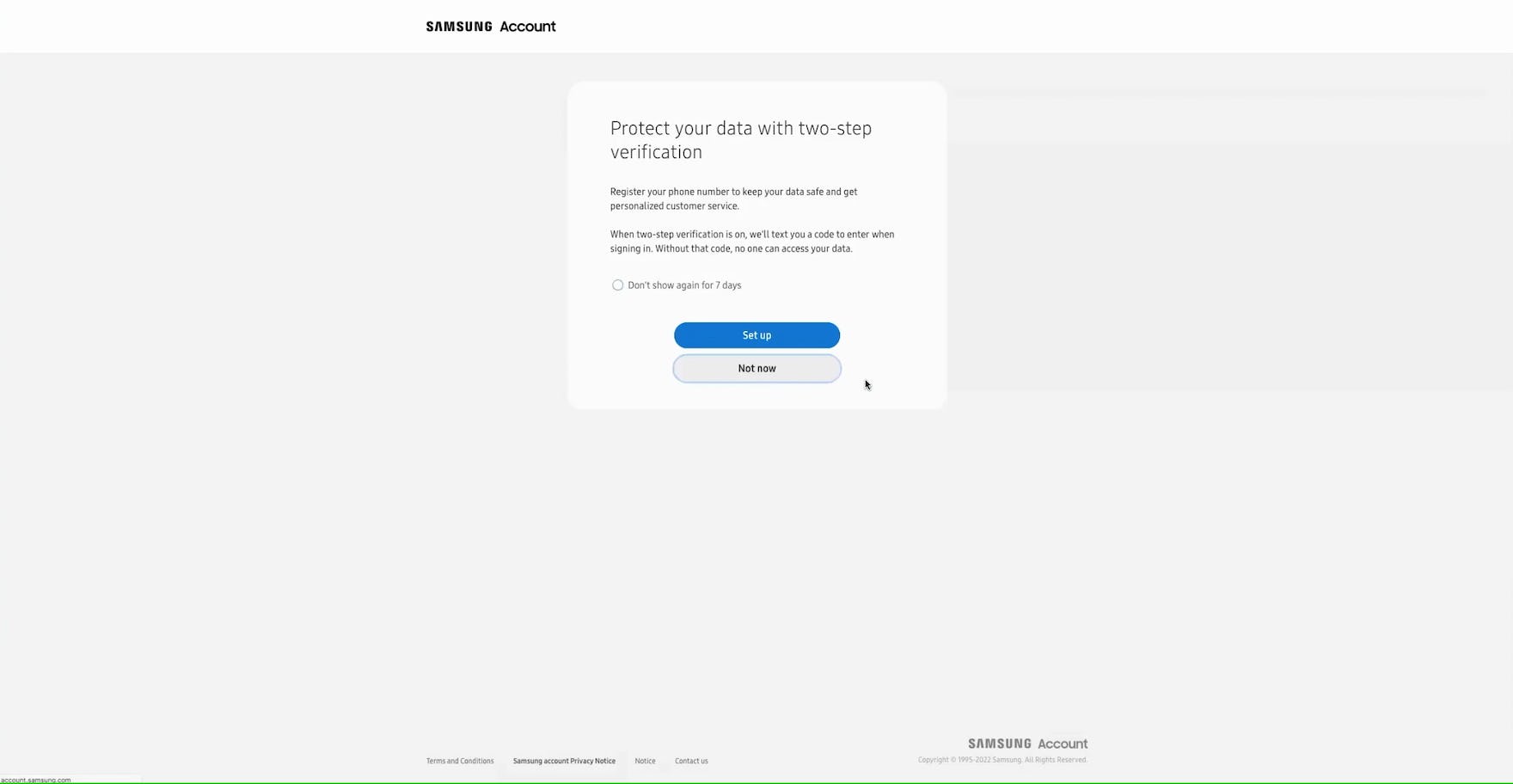

“I do like the two-step though…I feel like it’s secure when they send you a text or email, I think it’s secure.” When creating an account at Samsung, this participant appreciated the invitation to add two-step authentication, perceiving it as a beneficial layer of additional security.

“I’d say maybe a few years ago I would be a little bit annoyed with it, but I actually not annoyed with it anymore. I’d say in the last two or three years I’ve put double security on…a lot of things, just because it’s more secure, so I don’t mind it anymore. It’s worth the extra stuff to me.” This participant signing in at Walgreens shared that she appreciated the extra security afforded by two-factor authentication despite the extra steps involved. Another shared, “I think they’re good. I like that. It just checks your privacy better”.

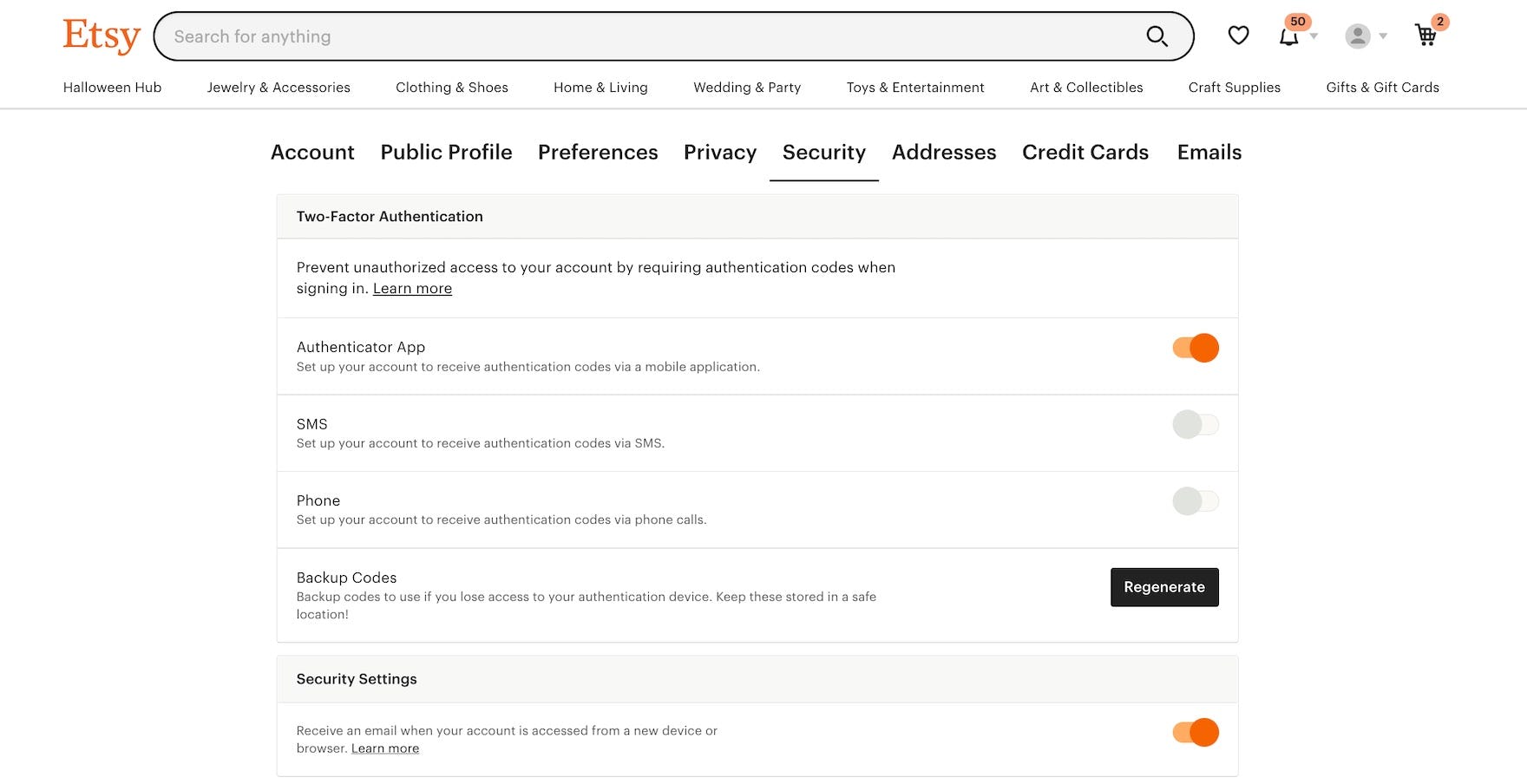

On Etsy, users can opt in to two-factor authentication via phone, SMS, or authenticator app. Additionally, users can keep tabs on their account usage by receiving an email whenever their sign-in is used.

Another way to further protect user accounts is to implement two-factor authentication, requiring confirmation from users’ account-associated email address or phone number before being able to sign in.

In practice, sites can adopt differing degrees of two-factor security, from requiring it only when users are attempting to sign in from a new browser or device to offering the ability to link their account information to a device-based authenticator app.

Requiring an email or SMS code in addition to — or instead of, in the case of “magic links” — user passwords does not entirely remove the risk of sign in issues, as users will still need access to the second-factor source.

However, they do substantially enhance account security while reducing the mental burden demanded by overly complicated passwords.

Moreover, in testing, while some participants appreciated and applauded the additional security afforded by two-factor authentication, others saw it as a burden, expressing that, while clearly beneficial for sensitive sites such as financial or health care accounts, requiring it to sign in to most e-commerce accounts was unnecessary.

For instance, one participant stated, “I admit, I do it with my email and with my bank, but it’s a little onerous. For most shopping websites, I don’t think it’s really necessary…I think it’s overkill for most sites”, while another admitted, “I kind of feel like it’s a pain in the butt. [If it were optional] I would opt out”.

Depending on the nature of account data collected, sites can consider making additional layers of two-factor authentication optional, allowing security-conscious users to opt in without burdening users who find some risk acceptable.

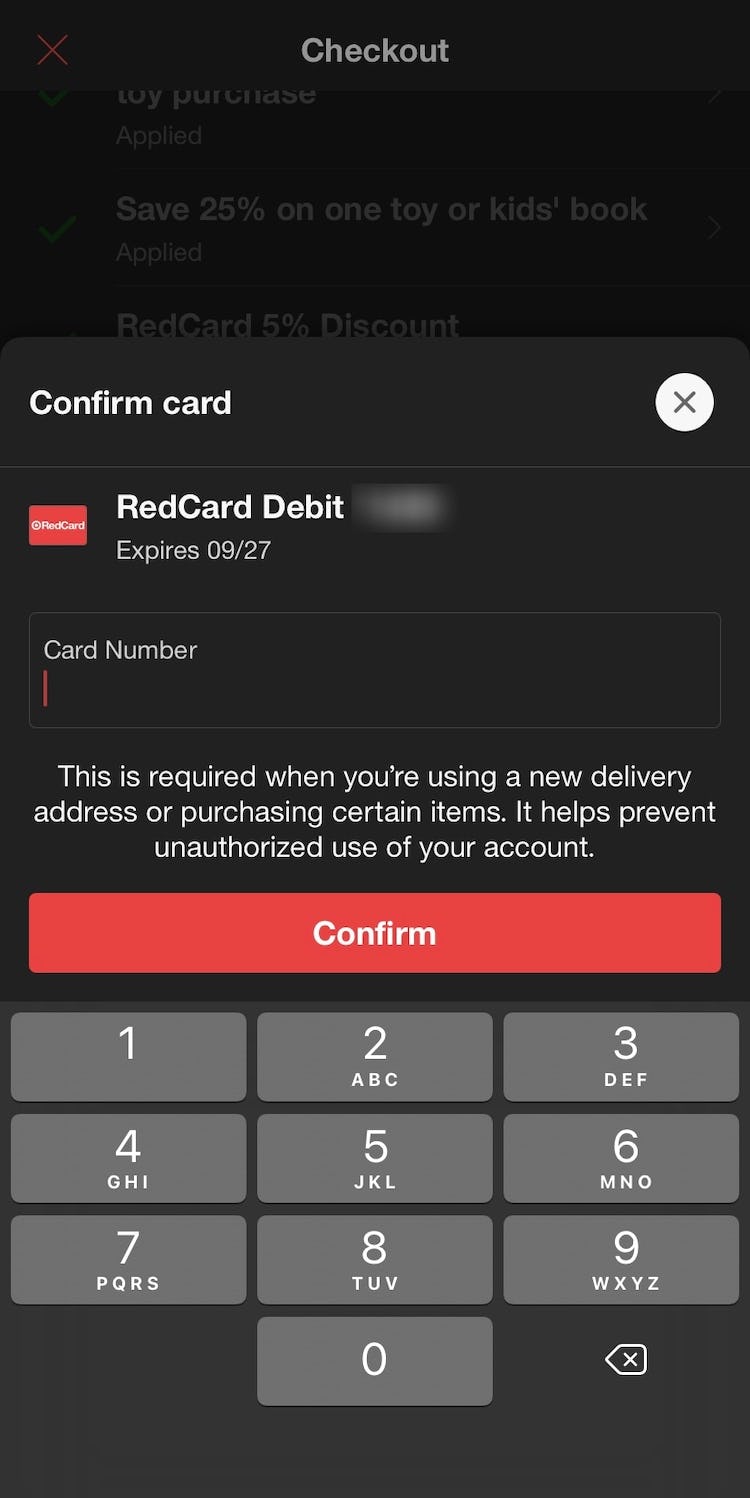

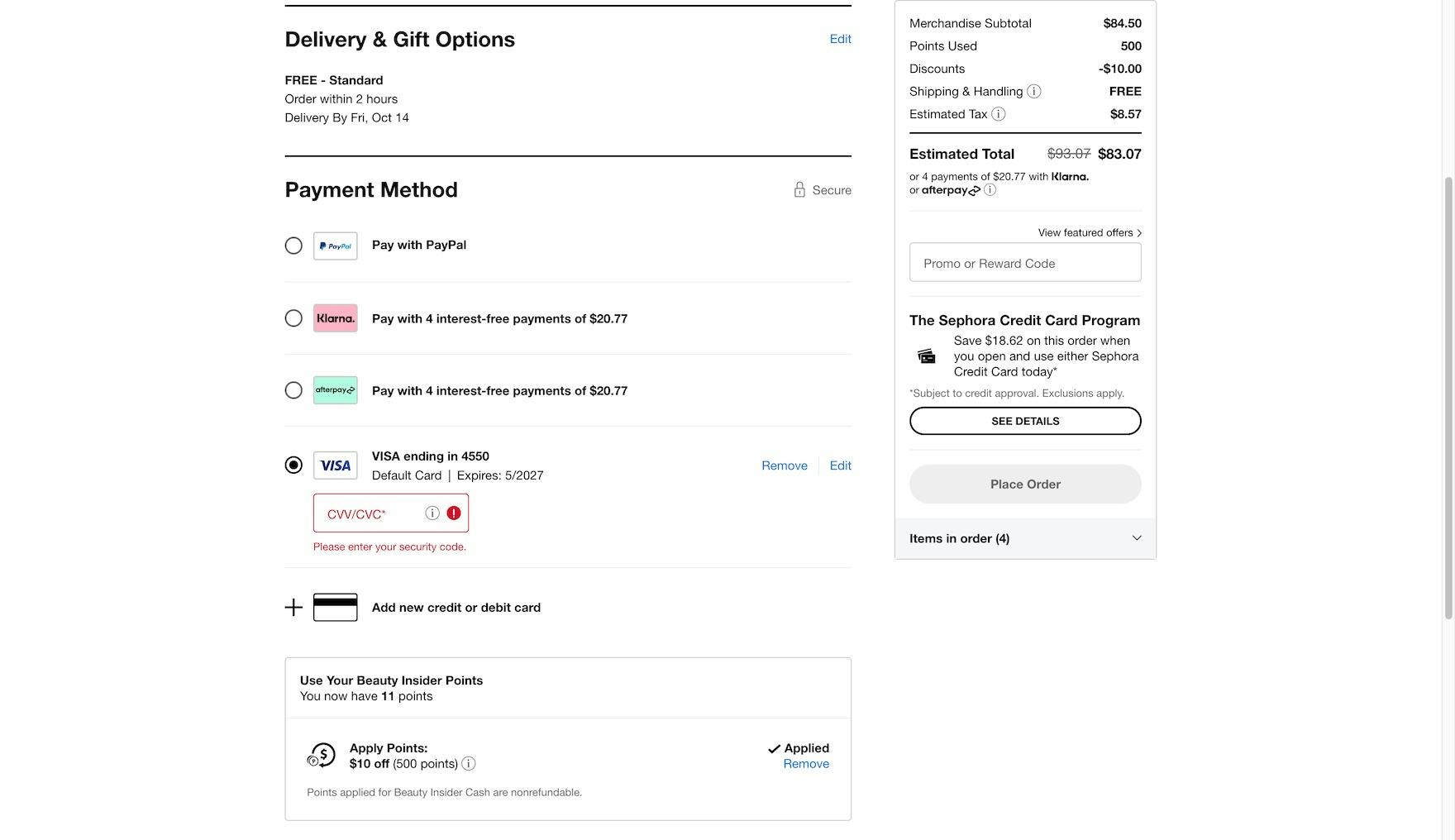

2) Requiring Users to Retype Payment Details if Sending to a New Address

Checking out at Sephora, users are required to retype the security code associated with their card when using a new address, which can prevent hackers from benefiting from unauthorized purchases.

If a hacker does gain access to a user’s account, sites can minimize the consequences of the breach by not allowing users to pay with a stored credit card if the purchase is being sent to a newly added address without first retyping credit card details - as seen in the two examples above.

This safeguard prevents hackers from sending orders to themselves with the victim’s stored payment methods and reduces the risk of serious repercussions.

If hackers are prevented from benefiting from fraudulent orders, the main consequences of an account breach are reduced to sending items to the user’s saved addresses (which can then be canceled or returned), viewing the user’s order history, or deleting the user’s stored information (as stored credit card data is not viewable from the account dashboard and card misuse on other websites is thus not possible).

Implement Technical Solutions for Account Security — Don’t Rely on Overly Complex Password-Creation Requirements

Sites must always take care to protect stored passwords — and all user data.

In practice, there are numerous advanced technical implementations that can minimize the risk of passwords being intercepted in transit or accessed directly from the site’s user database. Essentially, passwords complexity plays only part of the role in the risk of data breaches overall, and the responsibility of securing user accounts and should fall to the site itself — and not users. Yet 82% of sites in our e-commerce UX benchmark have unnecessarily complex password requirements.

Indeed, our testing revealed that, in practice, restrictive-password requirements carry serious checkout UX — and, thus, conversion rate — consequences. Some sites during our testing, saw up to 18% abandonment rates among all their existing account users, as these users tried to sign into their existing accounts but couldn’t due to forgotten passwords (and ended up abandoning during the password reset process).

Finally, it’s important to note that our recommendation here is not to accept low security standards — but rather to recognize the significant negative impact of password-complexity requirements on the user experience and suggest sites instead accept responsibility for keeping account information secure by implementing additional account security solutions, such as those as discussed in this article.

However, in the end the security impact and the implications of strict password rules may vary substantially depending on the site’s users and context, e.g., a retail site that collects minimal user data vs. an online pharmacy, financial application, or social network. Furthermore, even in an e-commerce context, different sites are apt to have varying security needs and tolerances.

Therefore, it is ultimately up to each site to determine what the minimum security requirements should be for their own unique context. Yet it’s important to keep in mind that any additional password requirements beyond a 6–8 character minimum has UX tradeoffs and will result in at least some users abandoning their purchase.

This article presents the research findings from just 1 of the 650+ UX guidelines in Baymard – get full access to learn how to create a “State of the Art” ecommerce user experience.