This is the 3rd in a series of 9 articles based on research findings from our e-commerce product list usability study.

We considered naming this article “the sort type all users want but zero sites offer” because category-specific sorting really is one of those rare instances where an obvious feature has somehow been completely overlooked by the e-commerce community. After all, it really shouldn’t come as a surprise that users would like to sort a list of TVs by “Screen size” or a collection of hard drives by “Storage capacity”.

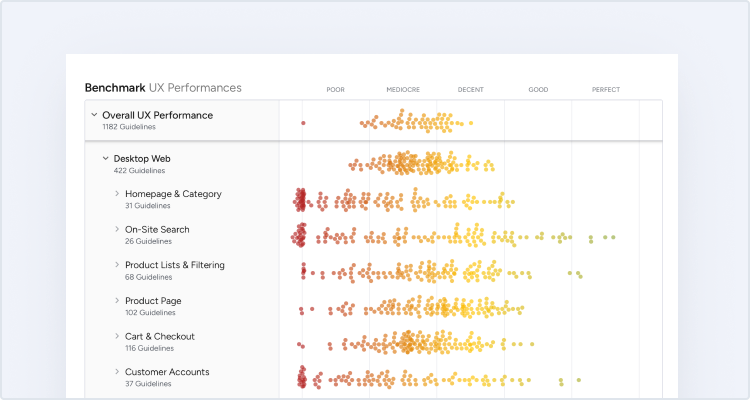

During our research study on product list usability the test subjects repeatedly sought out these kinds of category-specific sort types – however, to no avail since seemingly zero sites offer them. Even after benchmarking the product lists of 50 major e-commerce sites we have yet to find a site that truly offer category-specific sorting.

In this article we’ll outline our research findings on why category-specific sorting is so important to the user’s product finding abilities, and how it can be implemented.

A mock-up we’ve created of what category-specific sort types could look like at BestBuy. Here the three last sorting options – for TV screen size, refresh rate, and display depth – are available exclusively within the TV category while the other sort types are available site-wide.

Given that category-specific sorting is such an uncommon feature, let’s quickly define the term. By “category-specific sort types” we mean any sorting options that are only available in one or a few select categories (because they wouldn’t make sense as site-wide sorting options – they only make sense for the products within those particular categories). Examples include being able to sort suitcases by volume, fishing rods by length, pens by point size, hard drives by storage capacity and spindle speed, road bikes by weight, etc. It’s this category specificity that makes them different from common site-wide sort types such as ‘Best Selling’, ‘Relevance’, ‘User Ratings’, and ‘Price’, which are typically available for all products and categories throughout a site.

‘Soft’ Boundary Sorting vs ‘Hard’ Boundary Filtering

The differences between filtering and sorting may on the surface appear subtle. Indeed, many users mix up the terminology or use the terms interchangeably. However, the differences are in fact quite significant: Filters set the criteria for whether a given product is in- or excluded from the product list (i.e. what is displayed) whereas Sorting determines the sequence of those products (i.e. how it is displayed).

This makes Filters great for setting “hard” boundaries while Sorting is optimal for applying “soft” boundaries:

- Filters – Sets a “hard” boundary. Any product that doesn’t strictly fall within the selected value(s) will be cut off. It is a great way for users to exclude any products that don’t match specific criteria.

- Sorting – Applies a “soft” boundary. The products are ordered by the chosen sort type (in the case of category-specific sort types that typically means a product attribute). It changes the sequence of the products but doesn’t exclude any items, enabling users to still see items that fall outside their initial boundary.

Our product list usability testing showed that users need both hard boundaries (i.e. filters) and soft boundaries (i.e. sorting) for optimal control over the product list. Depending on the user’s knowledge of the product domain and their own needs and restrictions they may have very strict and 100% clear criteria the product must fall within, in which case “hard” boundary filters are appropriate.

However, in many cases users don’t have that strict criteria and sometimes they don’t even know what an appropriate filtering range would be, in which case “soft” boundary sorting is more suitable. For instance, the user might care about a product attribute without having a specific criteria for it, or they may not have the necessary domain knowledge to set meaningful cut-off points.

Case: The $2,000 Lightweight Road Bike

Let’s take an example of a user with a simple purchase preference: “I would like a lightweight road bike and my budget is $2,000.” Now, that wouldn’t be an unusual or odd request in a road bike store, but it would be a very difficult product-finding task at the 98% of e-commerce sites that don’t offer category-specific sort types, because the “lightweight” preference isn’t suited for a “hard” boundary filter (but instead needs the soft boundary of a sort type).

While there are plenty of sorting options available none of them are category-specific and none of them will help the user with their “lightweight” preference – even though the site clearly has weight information on their bikes (to support the “Weight (lbs)” filter).

Let’s play out the scenario to illustrate the issue. Note in the following how you can replace “bike” with your main product category and “weight” with any one of the primary numeric product attributes for that product category (e.g., capacity, power, speed, size, duration):

- The user starts out by finding the “Bikes” category and applies a “Bike type” filter of “Road bike”. The user now has a list of road bikes.

- Then, the user applies a “Price” filter defining an upper limit of $2,000. That’s easily done at most sites, and the specificity is well-suited for the hard boundary of a filter. The user now has a list of road bikes at $2,000 and below.

- Finally the user cares about the bike weight, and this is where problems arise. If a “Weight” filter at the lowest end of the range is applied, the user ends up with a very small selection of road bikes, and will still have to open all their respective product pages to figure out which one is the lightest. If a broader “Weight” range is applied (or no “Weight” filter is applied at all), the user ends up with road bikes that aren’t necessarily lightweight, forcing the user to open every product page and mentally keep track of which bikes are lightweight and which aren’t. Clearly neither of these approaches are ideal as the user must either apply overly restrictive filters (meaning they might miss out on relevant items), or make do with an excessively permissive “Weight” filter or no filtering at all (introducing a high degree of noise in the product list leading to needless friction in the user’s product exploration).

Now imagine in step #3, if the user had a category-specific sort type for “Weight”. If instead of applying “Weight” as a filter the user sorted the product list by weight (while keeping the $2,000 price filter in place), they would end up with a list of road bikes priced $2,000 or less sorted by lowest weight. The user would effectively have indicated their “lightweight” preference without having had to define highly precise cut-off points. Finally, the user would have a list of road bikes from lightest to heaviest costing $2,000 or below.

The “soft” boundaries of sorting essentially enable users to apply a preference to the product list without having to worry about striking some perfect magical sweet spot between an overly restrictive and excessively lax filter range. Yet filters remain relevant for things like the user’s specific budget limitation of $2,000 – this isn’t a mere preference. It’s by applying a combination of both “soft” (sorting) and “hard” (filtering) boundaries that the user is ultimately able to get what they are seeking: a list matching both the specific budget limitations of $2,000 while also having the “lightweight” preference applied.

Why Users Often Prefer “Soft” Boundaries

During usability testing the subjects often preferred the “soft” boundaries of sorting over the “hard” boundaries of filters. The road bike example illustrates why users in some cases prefer “soft” boundaries over “hard” ones – it alleviates them from defining cut-off points. Further investigation reveals 3 reasons users prefer the “soft” boundaries of sorting:

- Fear of missing out – The user may not want to set a hard boundary in fear of missing out on relevant products that fall just outside their defined range, hence many users prefer the soft boundaries of sorting.

- Lacks domain knowledge – The user may not know or feel like they have sufficient knowledge about the product domain (the natural spec jumps within the vertical, the implications of different product attributes, etc) to set appropriate cut-off criteria. In these instances the user will naturally find it more desirable to indicate their preference without having to define it through criteria they don’t fully understand.

- Unclear about own preferences – The user may not be entirely clear on their own preferences and restrictions (budgetary limitations, compatibility requirements, usage conditions, etc). Oftentimes users purchasing for themselves are willing to flex their criteria significantly once they start seeing what’s available and begin to understand the product domain better.

Setting specific criteria requires knowledge about the product domain (reason #2) – the natural spec jumps within the vertical, the implications of different attribute values, etc. – as well as knowledge about your own preferences and restrictions (reason #3) – budgetary limitations, compatibility requirements, usage conditions, etc. Both of these feed into reason #1, the fear of missing out on relevant items. If the user either lacks domain knowledge or is unclear about their own preferences (or both), they will tend to prefer “soft” boundaries because they would fear excluding potentially relevant products if they were to apply restrictive filtering criteria.

All of this is typically provoked by an information dilemma: the user has to set the “hard” boundary criteria before seeing the available products. So unless the user already has very good information about the product domain and their own preferences (prior to visiting the site) they often feel unconfident in applying such strict criteria. Few users want to fine-tune a product list if they don’t feel confident in accurately predicting the consequences of this fine-tuning.

Sorting Prevents Accidental Product Elimination

Sorting provide users a way to fine-tune the product list to their preferences without running the risk of accidentally eliminating relevant items. It thus helps solve one of the fundamental challenges users have when browsing an e-commerce site: somehow finding all the products that are relevant to their specific needs and preferences out of the site’s typically enormous product catalog.

In order to attain this highly curated list the user must narrow the product list down to a manageable size without discarding any relevant products in the process – they must at once be sufficiently aggressive in their filtering to reach a manageable product list without being so aggressive that they filter out relevant items in the process.

When the user can only filter and not sort by category-specific attributes they are limited to setting “hard” boundaries only. This leaves the user with two less-than-ideal options: either 1) apply the preferred range as filters and run the risk of accidental product elimination, or 2) loosen the preferred range to be more inclusive to avoid this elimination at the cost of ending up with a much poorer signal-to-noise ratio (due to numerous less relevant items suddenly being included).

Soft boundaries are very helpful in this regard because they allow the user to mainly browse a certain range without excluding (any potentially relevant) items outside it – enabling users to discriminate rather than eliminate.

Sorting Increase Domain and Site Insight

“Soft boundary” sorting can provide users with a better understanding of the product vertical and site catalog by revealing different “spec jumps” and “product gaps”. For instance, in the road bike example, it might be that the first three bikes in the sorted list cost $1,800 and weigh in at ~17 pounds (~7.5kg), and then there’s a jump in the list where bikes four through ten are 6 to 8 pounds heavier but also cost significantly less (e.g., weigh 22 pounds but only cost $900). This would help the user better understand the relationship between price and weight within the road bikes domain.

A mock-up we’ve created of what the earlier road bike example could look like with category-specific sorting for “Weight” and “Gears”. Sort types like these can help both novice and expert users gain better insight into the site as well as the domain they are currently browsing.

This is obviously very helpful to novice users because their lack of domain knowledge means they don’t instinctively know the natural “spec jumps” in the product vertical and might therefore inadvertently eliminate large clusters of perfectly relevant products. These users will therefore tend to prefer “soft” boundary sorting over “hard” boundary filters in fear of missing out due to a lack of domain knowledge, as explored earlier.

However, category-specific sorting can also help expert users despite them being intimately familiar with the “spec jumps” in a product vertical because it provides insight into the site’s catalog and any “product gaps” there might be in it. After all, just because the user knows a certain range of products exist they don’t necessarily know which of those products the site carries. By sorting instead of filtering, expert users get insight into which product groups the site carries within the vertical (and which they don’t carry).

Category-specific sort types can thus help increase novice users’ understanding of the product category (and any “spec jumps” within it) while simultaneously providing expert users insight into the breadth of the site’s product range (and any “gaps” within it).

Numerical Category-Specific Product Attributes

Category-specific sort types are appropriate in product categories where the products share one or more numeric attributes that users may have an interest in or preference for – such as the “Display size” of TVs or “Storage capacity” of hard drives. This is particularly true if the attribute is something where users don’t want to apply strict criteria or are unfit at doing so due to a lack of domain knowledge.

The numericality of the product attribute is important because it makes it well-disposed to sorting as the products can be ordered based on the natural progression of the attribute. Compare this to a non-numeric product attribute like ‘Color’ which can’t really be sorted in a sequence logical to most users. It simply doesn’t make sense to sort by discrete product features even if it is technically possible because there isn’t a natural progression or hierarchy for such attributes. For example, DSLR camera lenses can’t meaningfully be sorted by “Lens type” or “Camera mount” (as they have no natural progression or hierarchy), but it could make sense to sort the category by “Focal length” or “Angle of View”.

The closest we came to a meaningful category-specific sort type during testing was at Amazon which have a special “Release date” sorting option within their “Movies & TV” scope. The attribute is unique to the category and dates obviously have a natural progression. Unfortunately it is a rather ambiguous product attribute since it isn’t clear if it is the premiere date of the movie or the day the DVD version was released – something that tripped up numerous subjects during the usability tests.

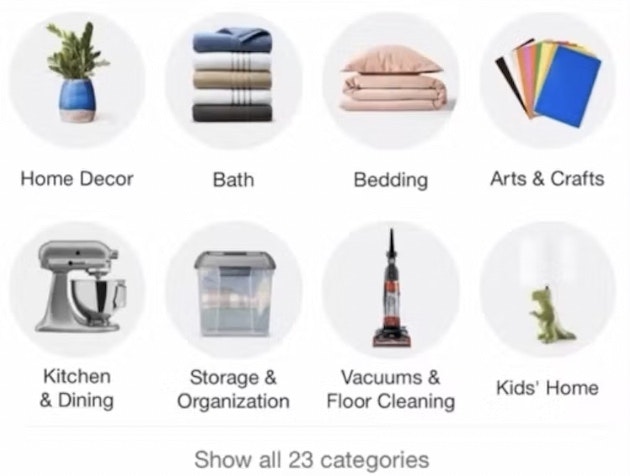

Many product verticals do, however, have such numeric attributes and category-specific sort types are therefore relevant to a wide range of domains such as consumer electronics, kitchen utilities, office supplies, sports and hobby equipment, hardware, and similar industries. There are some exceptions of course – in particular verticals that are driven mainly by aesthetics, such as home decor and apparel. These verticals generally have only a few or no important numeric product attributes and it therefore won’t necessarily be meaningful to implement category-specific sort types in them (although even in these domains, attributes such as weight and size may be important depending on the exact product type).

Curating the Category-Specific Sort Types

Determining which product attributes should be implemented as category-specific sort types is a fairly straight-forward matter: simply take the 3-5 most important numeric category-specific filters available in each category on your site and turn them into sorting options too. Let’s tackle some common questions that typically arise as a result of that statement:

- Why 3-5 attributes? To avoid overly long sorting drop-downs that induce choice paralysis. Although don’t get too stuck on the specific numbers, just make sure the number of sorting options don’t get completely out of hand.

- How do I identify which filters are the “most important”? Well, these filters should already be identified as the order of the filtering options should be determined on their relative importance. This importance may be arrived at through expert (human) judgement or programmatically through various proxies (filter popularity, number of products, feature impact on price, etc) – or a combination of the two. An example of a very important product trait would of course be ‘price per unit’ in categories where this attribute is relevant (i.e. where multi-quantity products are common, such as golf balls, copy paper, liquids, etc).

- Why numeric attributes? Because they have a natural progression that makes them suitable for sorting. (See the above section.)

- Why category-specific filters? The category-specific sort types should be provided in addition to the regular site-wide sort types such as “Price”. We assume you already have these in place and are here dealing with dynamically created sorting options that won’t be available site-wide. (Note: If category-specific filters aren’t already implemented, stop reading this article and implement them right now! Our usability testing revealed this to be one of the most fundamental features to the user’s browsing experience.)

- How do I turn the filters into sorting options as well? Well, with category-specific filters already in place, this is a simple matter of reusing the data powering those filters. After all, in order to be filterable the product data will already be fully structured and can therefore simply be reused for sorting purposes as well.

So in summary: We limit the number of category-specific filters to double as sort types to 3-5 attributes to avoid unruly and intimidating sorting drop-downs. Because of this restraint we obviously want to pick the most important product attributes to cater for the most likely use cases on our site. And we implement all of this by tapping into the data structures already in place for category-specific filters.

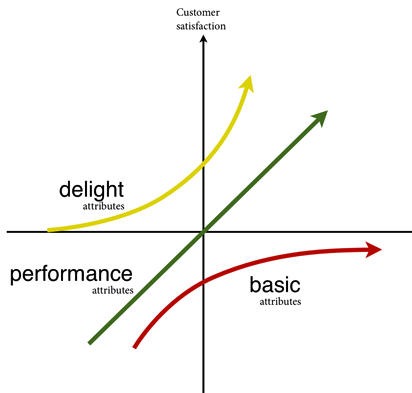

If familiar with the Kano model, the attributes to use as category-specific sort types will often be the “Performance” attributes within each product vertical.

The beauty of category-specific sort types is that they tap into investments already made in filters, effectively increasing the return on those investments. Because it’s a technical feature, it doesn’t require continuous data collection or curation (beyond what is already being done for the filters), and it’s therefore a one-time investment that permanently increases the value of the continuous investments made in collecting, curating and maintaining structured product attributes.

The most important filters within each unique product category can thus also be utilized as sort types in that category. (It should of course still be a filter as well – this is about giving users the ability to apply both “hard” and “soft” boundaries to product attributes of interest to them.)

Empowering Users with Category-Specific Sort Types

The user needs both hard boundaries (i.e. filters) and soft boundaries (i.e. sorting) for optimal control over the product list. When the user has good domain knowledge and a clear understanding of their own needs, “hard boundary” filters are appropriate. However, as we’ve seen throughout this article there are other times where the user doesn’t have this level of domain knowledge or strict criteria for their product needs, in which case “soft boundary” sorting will often be more suitable. Both “hard” and “soft” boundaries thus have valid usage scenarios and this alone justifies their implementation.

A major bonus of implementing both “hard” and “soft” boundary controls (i.e. filtering and sorting) is that users can then combine them. This affords the user a new level of control over the product list, enabling them to wield both “hard” restrictions and “softer” preferences onto the site’s product lists. Suddenly a rather complex statement like “I would like a lightweight road bike and my budget is $2,000” can successfully be applied, with both “hard” restrictions (i.e. “road bike” and “$2,000 budget”) and “softer” preferences (i.e. “lightweight”).

If you have category-specific filters, the data is already there (and if you don’t, you really should implement them!), ready to be reused for category-specific sort types as well. Category-specific sort types are thus a great opportunity to gain even more from the structured data you’ve invested so dearly in collecting, curating and maintaining.

A mock-up we’ve created illustrating category-specific sort types combined with faceted sorting.

Indeed, this may even be taken to the next level by combining category-specific sort types with scope selection in higher-level categories and on sub-category pages. This combines category-specific sort types with faceted sorting, allowing highly relevant and popular category-specific sort types to be displayed at (higher) category levels where all products don’t actually share the attribute to be sorted by. This would furthermore make category-specific sort types possible in search results despite some of the results not having the sorting attribute.

Sadly, category-specific sort types are a good example of just how neglected sorting is on e-commerce sites – numerous users want these sort types yet no sites offer them! It’s a rare example of an obvious innovation that e-commerce sites have yet to make. (Tip: you can see 46 different sorting interfaces from the top US e-commerce sites we benchmarked for this study.)

Category-specific sort types are ultimately about empowering users with the tools they need to reach the product selection they want and have it presented in a way that suits their unique interests. It’s an obvious opportunity to increase the return on existing product data investments, empower your users and get ahead of the competition.

This article presents the research findings from just 1 of the 650+ UX guidelines in Baymard – get full access to learn how to create a “State of the Art” ecommerce user experience.